Updated on June 2023

Achieving net-zero emissions means reaching a state whereby the activities of the company’s value chain result in no net accumulation of carbon dioxide and other GHG emissions into the atmosphere1. To keep global warming below 1.5°C, this state must be reached by 20502.

The term “net-zero emissions” should therefore be distinguished from “carbon or climate neutrality“, which is currently used by companies that offset their residual emissions with an equivalent amount of carbon credits, but which does not ensure that the company has sufficiently reduced its emissions upstream.

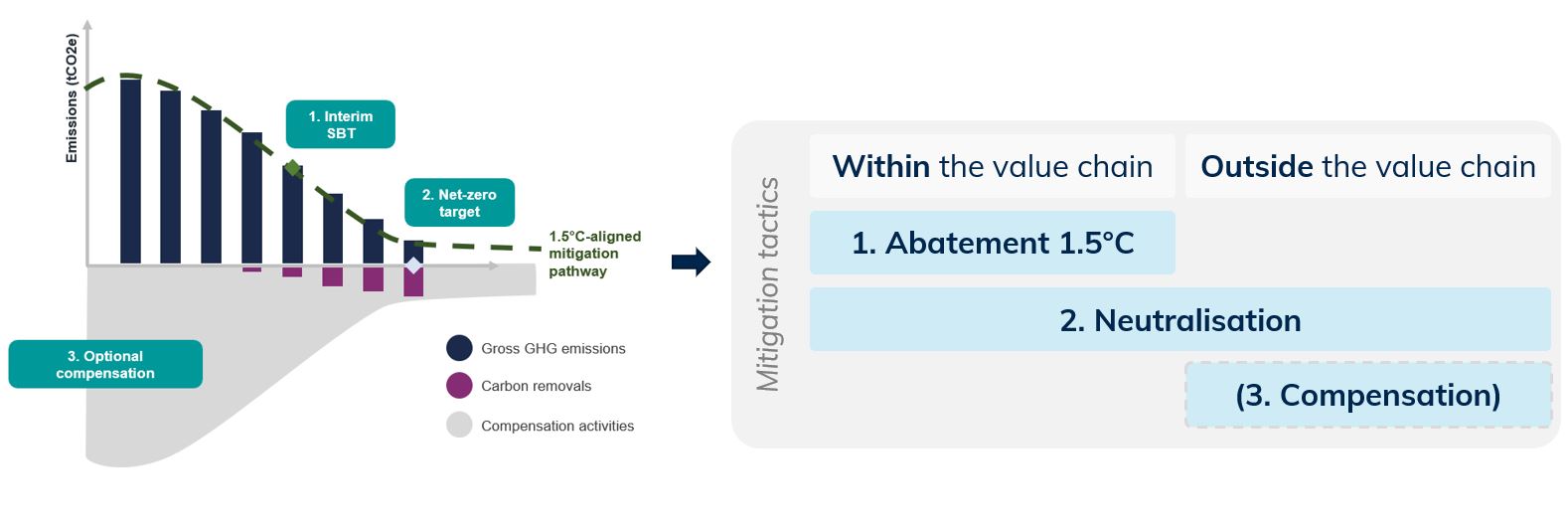

In concrete terms, achieving net zero emissions for companies in a credible manner requires three consecutives steps:

- Considering a company’s entire carbon footprint over the whole value chain, scope 3 included;

- Reducing emissions from the company’s value chain at a rate consistent with the objectives of the Paris Agreement, namely a 5% decrease in emissions annually;

- Sequestrating carbon to neutralize incompressible emissions. This means neutralizing the impact of any residual emission sources that cannot be eliminated by permanently removing an equivalent amount of atmospheric carbon dioxide.

It is essential that these three steps are followed consecutively. Relying solely on removals without reducing emissions first, or only considering scopes 1&2 emissions are grounds for being called out for greenwashing. A credible roadmap to net zero should detail in a transparent manner how each of these three steps will be achieved by 2050.

In April 2023, SBT has released its last version of its Net-Zero Standard that gives the international framework for companies to move towards “net zero emissions”, in line with the 1.5°C scenario.

In this third and last article of this series on how to create a credible net zero roadmap, we will cover the topic of carbon dioxide removals (CDR) as a solution to neutralize hard-to-abate, residual emissions (for previous articles see How to measure greenhouse gas emissions and and what scope to take into account “and “Reduction strategy: what ambition should we aim for in 2030 or 2050?“).

Furthermore, although voluntary offsetting is not accepted as a means of reducing emissions by the SBT Committee, this mechanism can be used temporarily by a company during its transition to Net Zero (i.e. between the time it undertakes to reduce its emissions and the time it reaches Net Zero).

Figure 1: Net zero strategy: different mitigation tactics

Carbon dioxide removals (CDR)

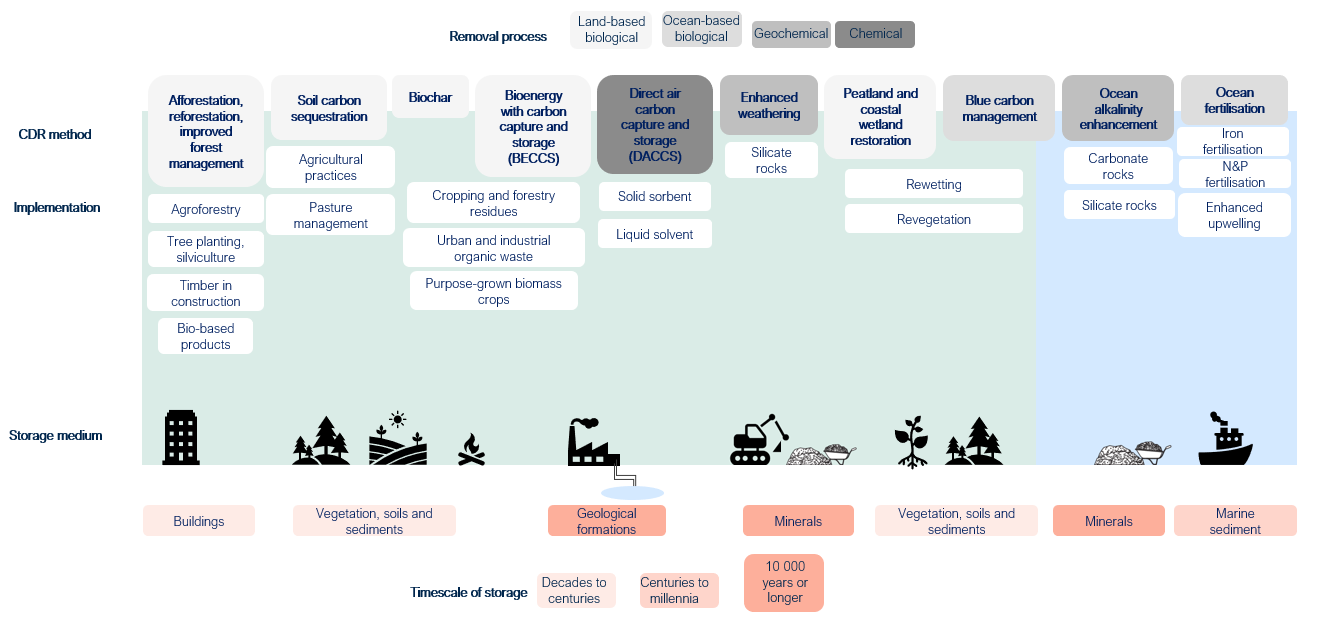

Carbon removal consists in the transfer of CO2 from the atmosphere via a process (sink) and the storage into a reservoir (pool). Two main types of sinks exist, biogenic sinks where CO2 is removed through natural processes (e.g. photosynthesis) and technological sinks where CO2 is removed through human-induced chemical reactions. Once removed, carbon must be stored permanently (or for centuries at least) in pools. Pools may be products, geological reservoirs, land and oceans.

Carbon removals can be grouped based on their sink and pool. It is important to handle each type of removal accordingly and with caution as they each differ in terms of maturity, permanency of the storage, accuracy of the quantification, co-benefits, etc. For example, the image below shows that different CDR methods vary strongly in terms of duration of the storage, ranging from decade for certain option, to millennia for others.

CDR methods each have their own limitations, technological removals for example are not mature yet and are still expensive. Land-based biogenic removals, such as carbon farming or afforestation are more mature but show limitations in terms of quantification and permanence.

The precise description of accepted neutralization projects and the minimum criteria required (permanence, social and environmental guarantees, etc.) are currently being specified by different standards (Carbon Removals Certification Framework, Article 6.4 of the Paris Agreement, SBTi Net-Zero Standard and GHG Protocol).

Voluntary compensation

The concept of offsetting is derived from emissions trading schemes. Under this approach, organisations can purchase carbon credits that guarantee that corresponding emissions have been avoided or sequestered, usually by another organisation, in a project outside the scope of the buyer’s emissions inventory. Offsetting based on such projects, usually located in transitional or developing countries, allowed the financing of emission reduction projects in countries that were not subject to an emission cap under the Kyoto Protocol.

Today, however, the situation has changed. Since the Paris Agreement in 2015, all industrialised, transitional and developing countries must cap their emissions and regularly review their level of reductions’ ambition. So there is no longer really an “elsewhere” where industrialised countries or organisations can relocate their reduction efforts. On the other hand, the science is clear that the reductions needed are significantly greater than those projected at the time of the initiation of the Kyoto Protocol: global emissions must reach “net zero” shortly after 2050. Relying on reductions outside one’s own perimeter therefore only postpones the challenge of reducing one’s own emissions.

The role of voluntary offsetting in the context of setting Net Zero SBT targets for companies is complementary but optional. Further details on certain aspects, including the definition of a reference carbon price, are under discussion.

Do you want to take your climate strategy a step further and become the first Belgian company to commit to a scientific Net Zero goal? Contact our experts.

1 https://sciencebasedtargets.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Towards-a-science-based-approach-to-climate-neutrality-in-the-corporate-sector-Draft-for-comments.pdf

2 However, the SBT initiative specifies the obligation to set an intermediate target before 2050.

Get in touch with our experts

Contact us