On 30 September 2020 – 494 days after the elections – the 7 ‘Vivaldi’ parties concluded negotiations on the new Government Agreement. The outcome contains a number of measures to accelerate the climate transition, such as a green tax shift, significant investments to ensure a performing railway system, and a commitment to phase-out non-zero emission cars (starting with company cars). The new federal government also explicitly supports the ambitious EU climate objectives put forward by European Green Deal, and commits itself to a 55% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions – in the context of its own competences. But how does this 55% reduction ambition compare to the current Belgian reduction objectives? And what would it require in terms of additional efforts?

The Belgian climate objectives are linked with the EU climate policy architecture

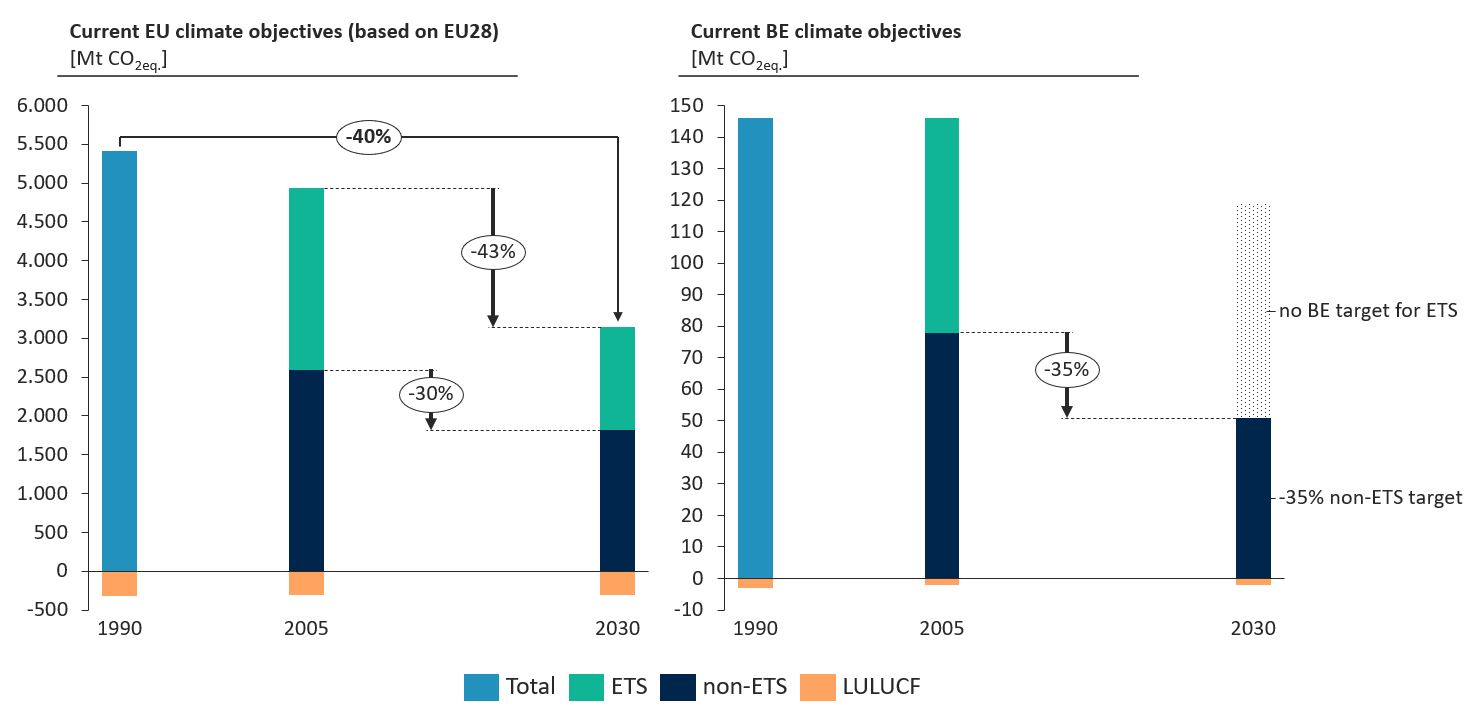

To understand and compare both reduction targets, one needs to take a closer look at the European climate policy architecture. At the EU level, overall reduction objectives are always expressed compared to 1990 emission levels. Currently, the EU has committed to reduce overall emissions with at least -40% by 2030 compared to 1990. The required effort is then divided over three different pillars: the EU ETS (covering power, industry and aviation), the non-ETS (covering transport, buildings, agriculture and waste) and the LULUCF pillar (covering land use and forestry). For the EU ETS and the non-ETS pillar, separate reduction targets are set compared to a 2005 baseline. The objective of the EU ETS is translated into a EU-wide, decreasing cap (-43% by 2030 compared to 2005, no national targets), and the objective for the non-ETS pillar (-30% by 2030 compared to 2005) is further divided in differentiated, national binding targets (for Belgium: -35% by 2030 compared to 2005). The figure below illustrates the current EU and Belgian climate targets:

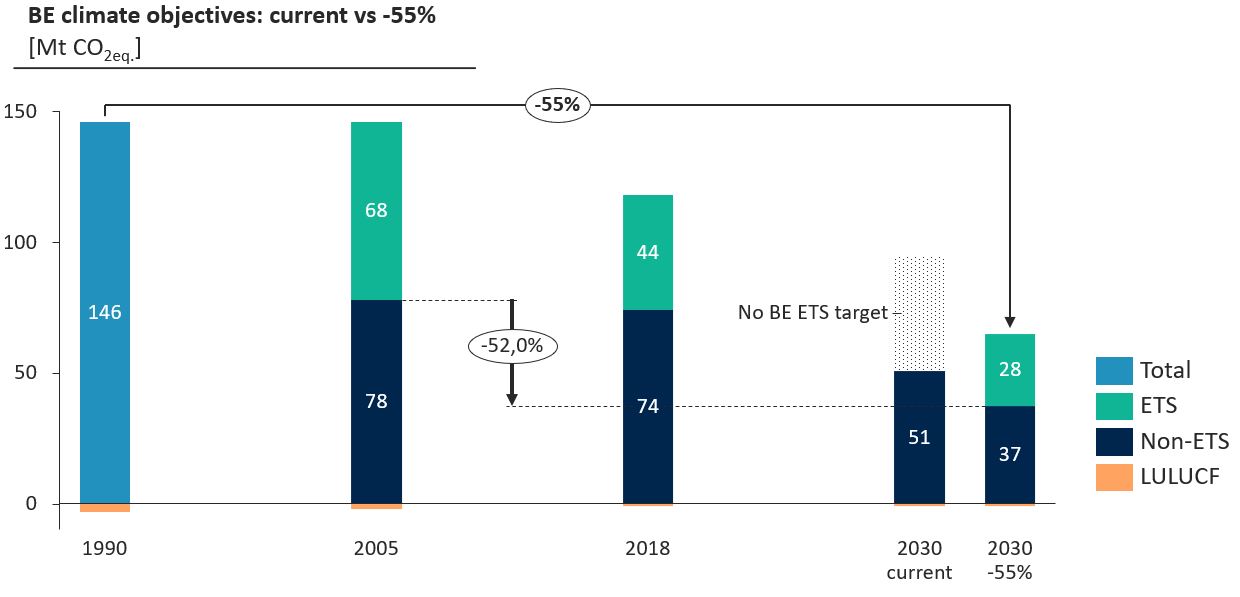

The European Commission has recently proposed to increase the overall EU climate objective from “at least -40%” to “at least -55%” reductions by 2030 compared to 1990. It has also identified different options to achieve this target, from a continuation of the current architecture (ETS + non-ETS + LULUCF) to deeper reform that could see the non-ETS pillar (including national targets) disappear. It is expected that a decision on these different options will be taken in the course of 2021. A report by Agora Energiewende1 has found that a continuation of the current architecture could result in a Belgian non-ETS reduction target of approximately -52%.

How does the federal -55% reduction commitment compare to the current Belgian reduction objectives?

The new federal Government Agreement is not 100% clear on the scope of the -55% reduction objective. However, given that it is mentioned in the context of the similar EU -55% target, we assume that is based on the same target year (2030), base year (1990) and scope (economy-wide). The exact implications would depend on how the effort is distributed between the ETS and the non-ETS pillars. If we assume that the reductions for the non-ETS sectors would have to be increased to -52% (in line with the Agora Energiewende report), this would result in the following:

What additional efforts would it require?

It’s clear that achieving a Belgian -55% reduction target requires a significant step-up in efforts compared to historical trends and the current objectives, both in the ETS as in the non-ETS pillar.

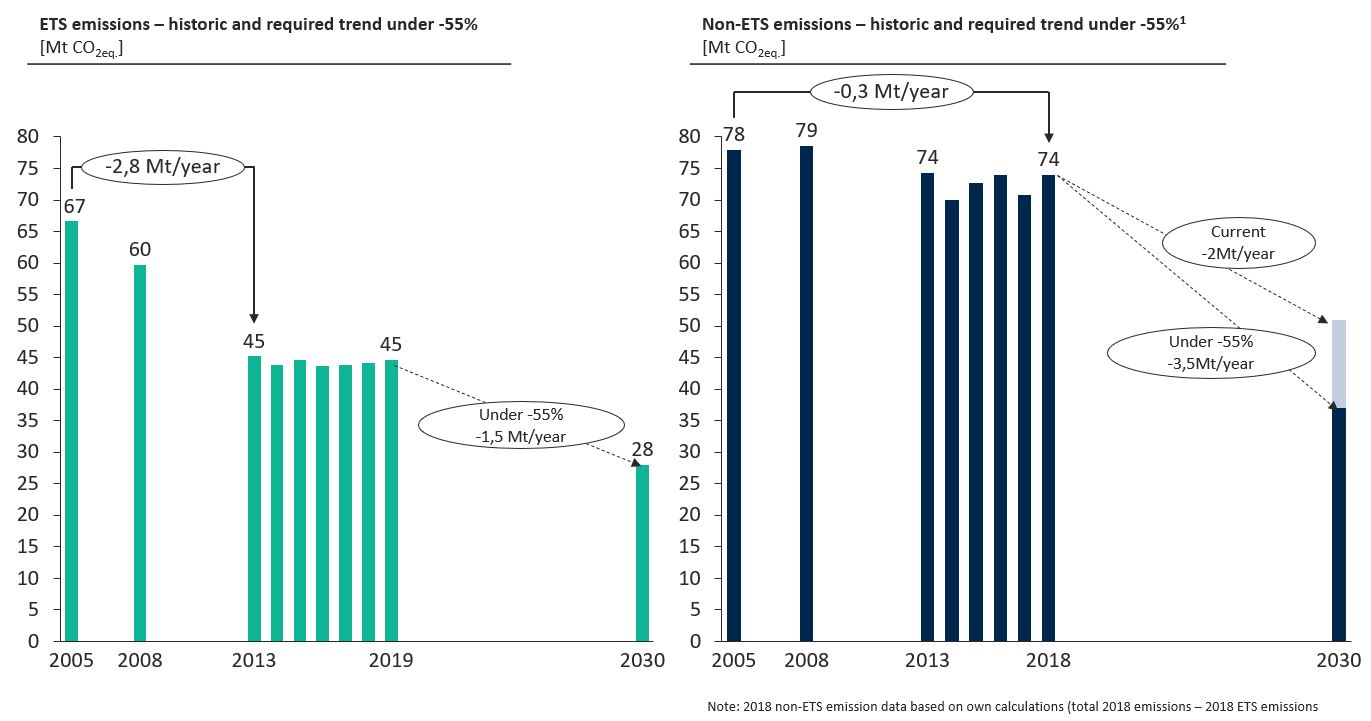

Assuming the split of efforts between both pillars as described above, annual reductions in the non-ETS sectors would have to increase from 2 Mt CO2eq./year (under the current objective) to 3,5 Mt CO2eq./year (under a -55% objective), almost a doubling of the effort. Compared to the historical trend (on average 0,3 Mt CO2eq./year reductions since 2005), reductions would have to be increased tenfold.

The ETS sectors would have to reduce their emissions with +- 1,5 Mt CO2eq./year between now and 2030. Although these sectors have achieved large reductions between 2005 and 2013 (partially due to closures, partially due to mitigation efforts), emissions have remained relatively stable since then. Taking into account the fact that part of the nuclear phase-out will be (at least partially) covered by new gas-fired power plants, the lack of low-hanging fruit (coal & lignite plants) compared to other EU countries, and the expected investments in new, large chemical plants in the Port of Antwerp, emissions are expected to increase again without additional efforts, highlighting the challenge to achieve deep reductions in line with a 55% reduction target.

Conclusion

Achieving a -55% reduction objective in Belgium would require a disruptive trend break compared to the stabilization in emissions since 2013, both in the ETS as in the non-ETS pillar. This will only be possible through a deep transformation in all sectors, to which all actors – both public and private – will have to contribute. We see encouraging developments both at the technological level (e.g. continued decrease of renewables prices, breakthrough of EV technology) as the societal level (increased awareness on consumer behaviour impacts). Furthermore, the strong commitment of the EU Commission and other member states (including the dedication of significant budgets) is expected to accelerate the low-carbon transition in the EU. These developments will have to be complemented by strong action from Belgian households, companies and policy makers. The measures that are announced in the federal Government Agreement are certainly a welcome step in the right direction. However, as many of the levers to drive the transition are regional competences, a strong commitment from and effective coordination between all Belgian governments – both federal and regional – will be needed to make a –55% reduction possible.

Author: Pieter-Willem Lemmens

Get in touch with our experts

Contact us